History of Claybank

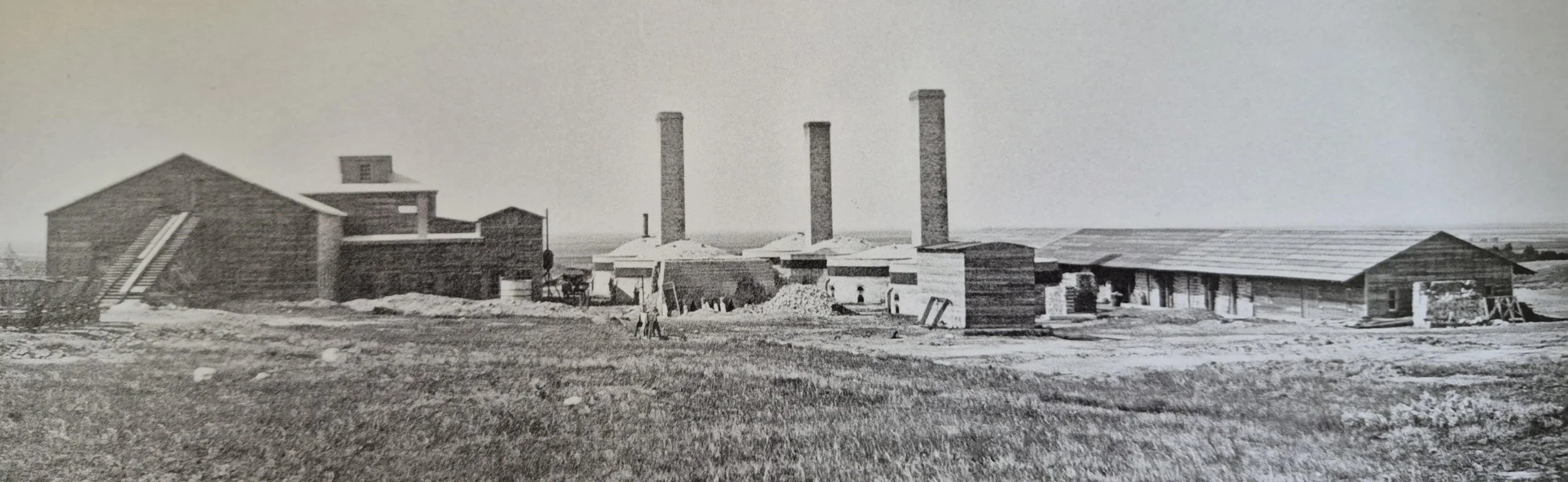

The Claybank Brick Plant, a National Historic Site of Canada, operated from 1914 to 1989 near Claybank, Saskatchewan. It was a major producer of both fire brick and face brick, playing a significant role in supplying refractory products to the railway, oil refining, power generation, and metallurgical industries. Its distinctive face brick was also widely used in buildings across the Prairies and beyond. Today, the plant showcases key structures and equipment from its early 20th-century founding.

Acknowledgement: This history is based on a 1992 report entitled “The Development and Operation of the Claybank Brick Plant: 1886-1989” by Saunders, Richan, and Associates

-

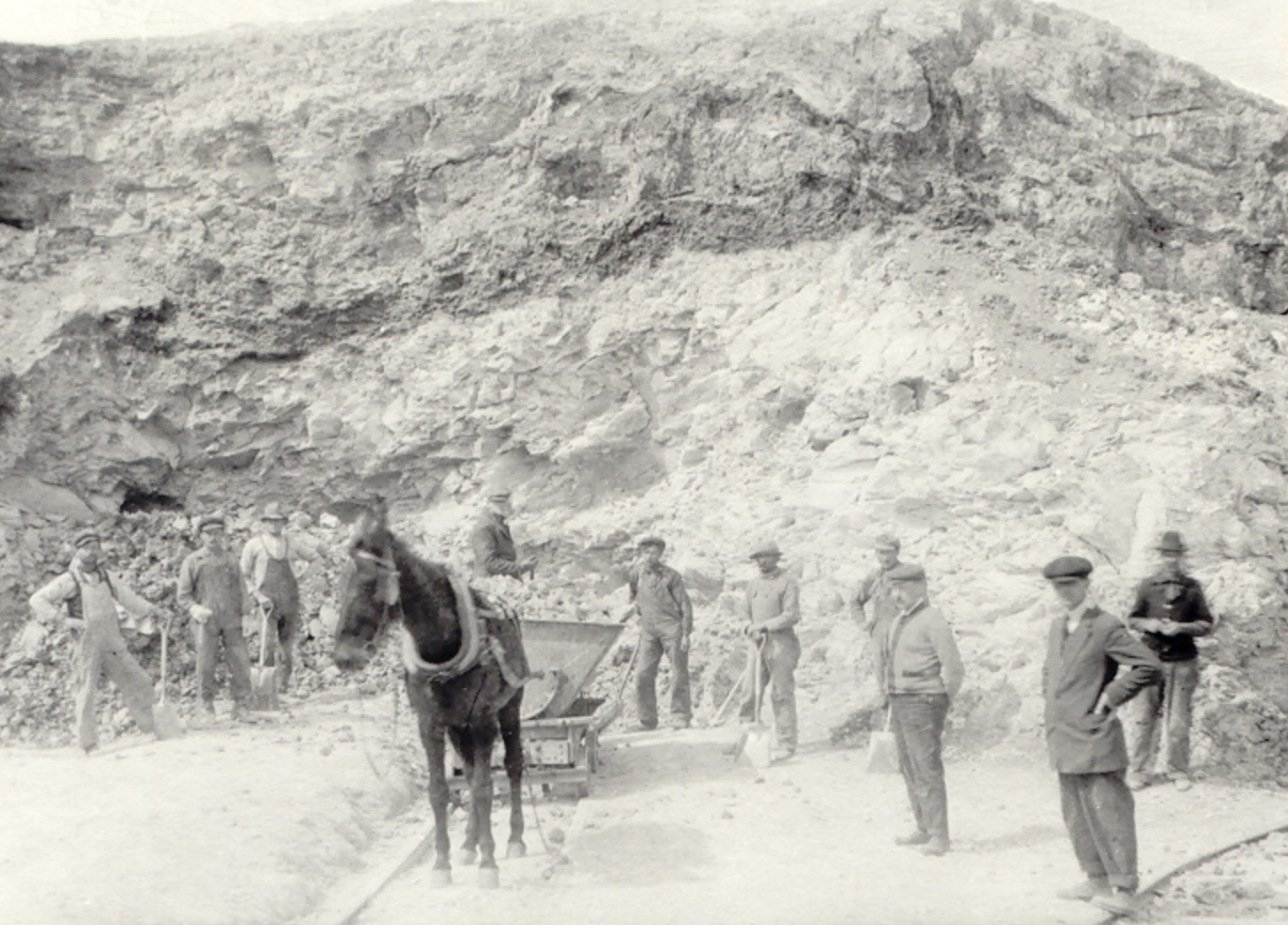

The first recorded discovery of clay deposits in the Dirt Hills was made in 1886 by local homesteader Tom McWilliams, who applied to the federal government for permission to mine the clay. At the Claybank site, he found a rare deposit of high-quality refractory clay. The heat-resistant clay was ideal for manufacturing fire bricks. McWilliams extracted the clay sporadically over several decades, selling it to brick manufacturers in Moose Jaw. In 1904, he entered into a formal agreement with the Moose Jaw Fire Brick and Pottery Company.

-

The Moose Jaw Fire Brick and Pottery Company was formed in 1904 by five prominent Moose Jaw citizens: J.H. Kern, a real estate agent and company president; Edward Matthews, a financial agent, alderman, and former mayor; Arthur Hitchcock, a land speculator, developer, and local banker; and two local doctors, Charles Turnbull and J. McCulloch.

The company acquired the McWilliams homestead along with several nearby clay deposits. However, transporting clay by horse and wagon from the Dirt Hills to Moose Jaw—a distance of about 50 kilometres—posed a major challenge and limited the potential for serious development.

That changed in 1910 with the construction of a Canadian Northern Railway line through the region. With rail access now in place, plans were made to build a brick plant next to the clay deposits, eliminating the need to haul materials long distances. When the town of Claybank was established along the railway, a spur line from the plant to the town site gave shareholders direct rail access to wider markets.

To move ahead with construction and production, the company reorganized under a new name—Saskatchewan Clay Products—in 1912, and purchased the remaining shares from Tom McWilliams.

-

Construction of the brick plant began in 1912 and was completed by 1914. However, a combination of economic recession in 1913 and the outbreak of World War I the following year forced the plant to close until 1916. Once conditions improved, operations resumed. Shortly afterward, the company reorganized once more—this time under the name Dominion Fire Brick and Pottery Company.

-

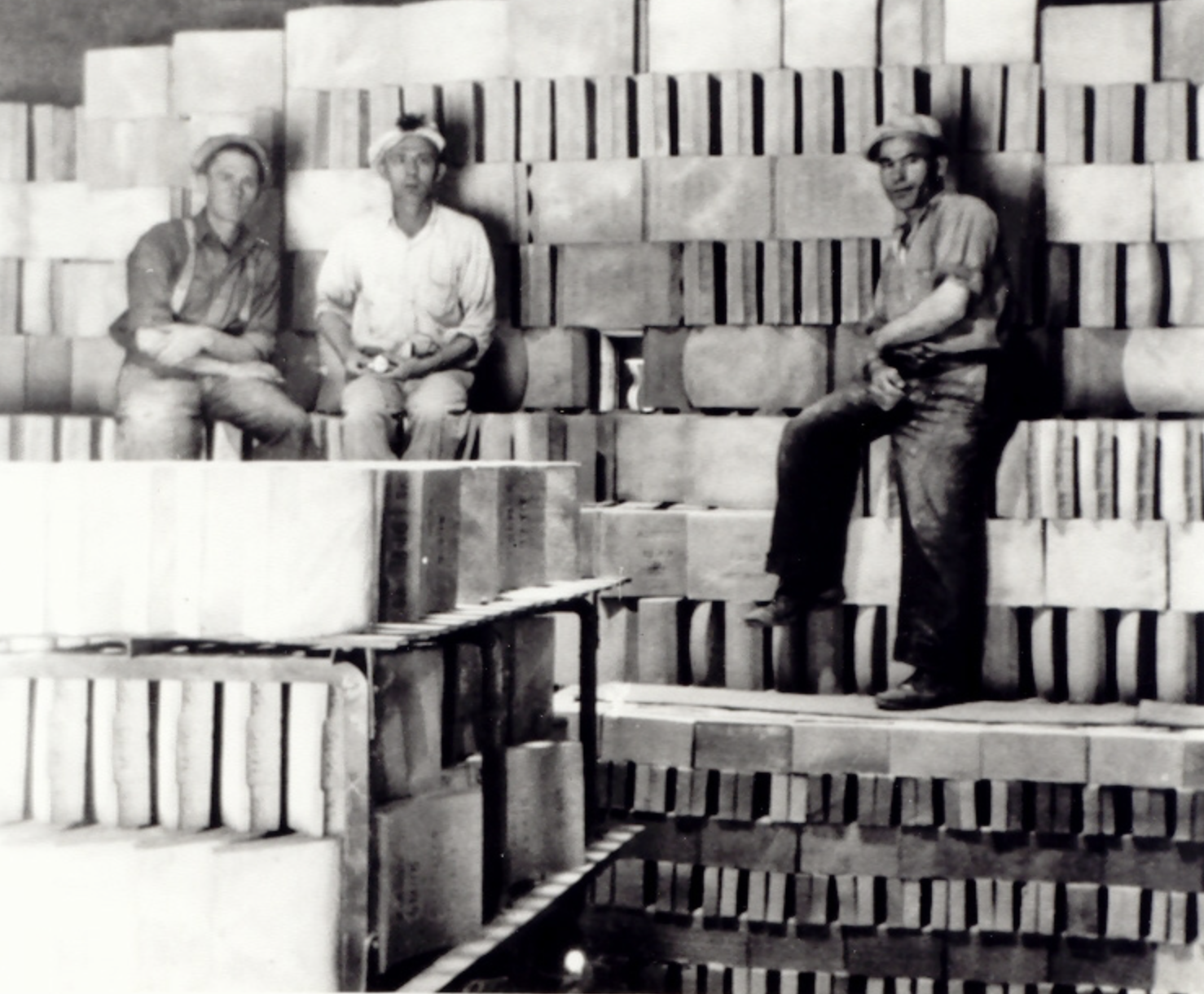

When brick production resumed in 1916, the new management introduced a new product line: face brick. This type of brick, used in building construction, quickly gained attention. The face brick manufactured at the Claybank plant appeared on many of Saskatchewan’s most prominent public buildings. Schools, churches, courthouses, government and commercial buildings, hospitals, theatres, and private homes were all faced with the distinctive T-P Moka or Ruff-Tex bricks made at Claybank. The quality became so renowned that even the new central tower of Quebec City’s Château Frontenac was faced with Claybank brick.

In many ways, the 1920s marked the Golden Years of the Claybank Brick Plant. Demand for high-quality fire brick was strong, especially from the railways and industrial sectors. At the same time, their new line of face brick became increasingly popular with builders and architects. Thanks to a growing customer base and a diverse product line, the company was well-positioned to weather the challenges of the Great Depression during the 1930s.

By the 1950s, the Claybank Brick Plant had grown into the largest clay products facility in Saskatchewan, surpassing the province’s other major brickworks at Bruno and Estevan.

-

In 1954, the Claybank facility was sold to Redcliff Pressed Brick, an Alberta-based company. This marked the transfer of ownership and management from the original founders in Saskatchewan. The following year, A. P. Green Fire Brick Company, located in Mexico, Missouri, acquired a controlling interest in Redcliff’s Saskatchewan operations. Post-war industrial changes significantly reduced the demand for refractory brick, especially in markets like locomotive refractory brick, which became obsolete with the railway industry's shift to diesel engines. During this period, six of the ten old coal-fired down-draft kilns were converted to use gas heat. While this increased the efficiency of fire brick production, it also led to the closure of coal-fired kilns. As a result, the company could no longer produce its high-quality T-P Moka face brick, which relied on coal impurities for its unique color. Because A. P. Green had little interest in face brick production, this product line was discontinued during the 1960s.

-

In 1971, A.P. Green Refractories Ltd.—then North America’s largest producer of refractory brick—officially acquired the Claybank operation as part of a corporate restructuring. The company, which operated brick plants globally, continued producing fire brick at the Claybank facility until 1989. That year, corporate downsizing led to the complete closure of the Claybank operation. In 1992, the facility was donated to the Saskatchewan government, which accepted it through the Saskatchewan Heritage Foundation.

The Claybank Brick Plant was a successful small industry based in Saskatchewan, known for its high-quality refractory brick production. Its early success can be credited to strong management, consistency among key staff, and the development of top-grade refractory and face brick products. However, as the industry and market evolved and new technologies emerged, the company underwent restructuring that eventually led to the plant’s closure—ending nearly 75 years of continuous operation.

While the facility saw some modernization, much of it still reflects the effective use of 19th-century brick manufacturing techniques that remained in use well into the 20th century.